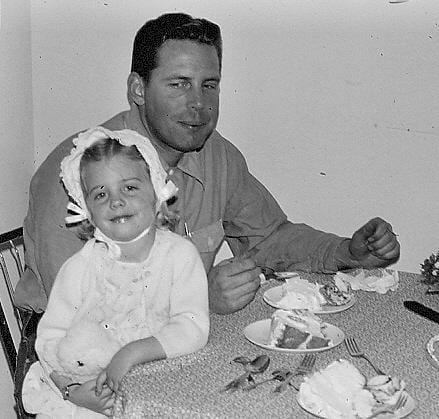

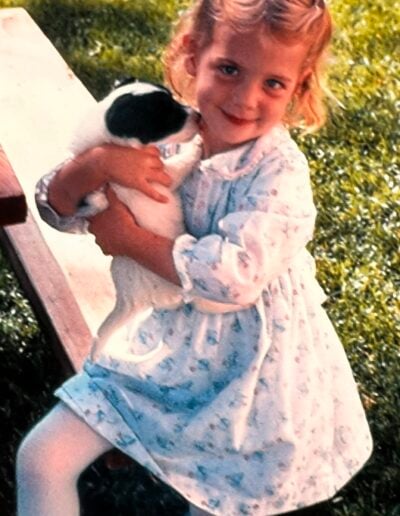

One of my earliest memories is also one of my fondest memories. When I was tucked into bed, my mother would come into my room to tell me goodnight. She was swift and efficient about it because she knew that she was simply the opening act. The headliner was my father. He would stand in the doorframe to my room, and the warmth that I felt upon seeing his face filled my heart like a small coal stove glowing in a cold, stone kitchen.

I cared deeply for my mother, but it was my father with whom I felt a kindred spirit. He was a sweet soul with a tender heart. My family was part of a small, strict religion, and there were many times when I did something wrong that dictated a spanking. But nine times out of ten, he just couldn’t bring himself to do it.

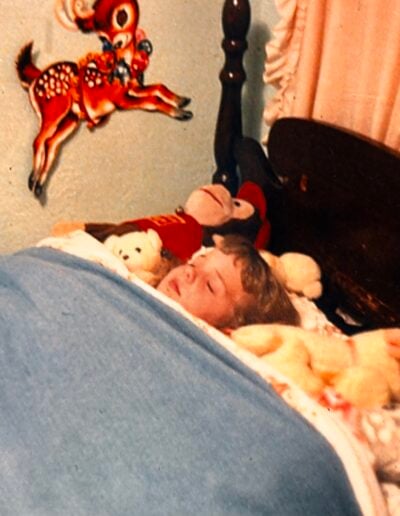

At bedtime, when my mother left the room and tagged my father in, our routine would begin. First, he would line both sides of my little body with my beloved stuffed animals. My bed was pushed against a wall, and that side of the bed had the sheets tucked in military tight. My father would take the sheets on the other side of the bed and pull them so tight across my body, I couldn’t lift an arm, a hand… hell, even a finger. Then he would sit next to me and tell me stories, read a book to me, or a combination of the two.

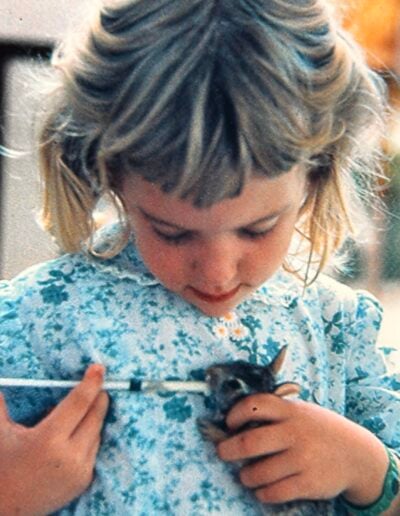

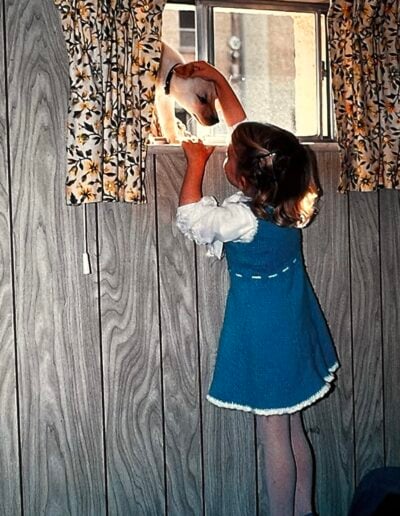

After my father tucked me in, a good twenty minutes of animal stories would follow—books with simple, whimsical watercolor illustrations. Dad and I shared a love of animals and saw every furball with the same set of eyes. There were slight moves an animal could make and we would both see it at the same time, and it would tickle us in equal ways. The wiggle of a cat’s butt in anticipation of a sneak attack. The guilty look a dog would display when you told him to stop barking, yet he got in one more little woof. The way a gopher chews, a bird hops, a mouse stands on its hind legs. Dad and I saw every little gesture, every flick of the ear, and every slow closing of the eyes in disapproval, and it pleased us to no end.

But my absolute favorite stories were the ones Dad told me of when he was a boy. There were three stories that I would endlessly request. The first was of his dog, Scamp.

My young father and Scamp ventured into the woods one afternoon, much further than they were allowed. He was determined to make it to the creek, knowing full well how far outside of the authorized perimeter the water flowed. Ever loyal, Scamp was right on my father’s heels… until he wasn’t. Dad noticed the absence of leaves crunching behind him and turned to see that Scamp had scampered off. But just as he turned, Scamp came out of the woods as though Bigfoot was chasing him and plowed into my father, knocking him into the creek. The water was shallow enough that Dad wasn’t in jeopardy, but it was deep enough to fully submerge him, soaking his clothes and hair. Combine that with the fact that he had ventured much further than was allowed, and had limited time to make it to dinner, he knew there was no way he would dry by the time he got back to the house. So my father had to suck it up and tell his mom the truth. He said it was the longest walk he’d ever taken. At the house, his mother was furious, yet amused. She spared him further retribution, correctly guessing that the walk of shame was enough punishment.

The second story involved a raccoon he’d found, abandoned by its mother as a kit. Dad bottle-fed him and named him Rocky. Every day, Rocky waited for Dad to come home from school, then followed him through every chore. One night, Dad snuck Rocky to the dinner table, safely tucked under his shirt. He was sure that he had outsmarted his mother’s curious gaze, until a slender, long-nailed paw slid up through the buttons on his shirt to gingerly gather a grape off of his plate. His mother simply looked down at her plate of food and commented in his direction, “Your nails could use a trim.”

Dad said that Rocky stayed with him until he began to get randy… he reached sexual maturity and went hunting for the ladies. When Dad would get home from school, Rocky would still occasionally venture down from the trees to visit, but eventually the raccoon stopped answering to his name altogether, and Dad stopped calling for him.

And then there was the horse with no name… my favorite bedtime story. My father was driving my grandfather’s car to and from a summer construction job when he saw a sign that said, “Horse for sale.” On a whim, my father followed the signs, and upon arrival, he offered the seller a ridiculously low price, not anticipating an acceptance.

When the offer was accepted, and the money exchanged, my father was left with a tough decision: how to get the horse home. He didn’t want to abandon the car, nor did he want to abandon the horse. So he fit the bridle and the lead on the horse, pulled him next to the driver’s-side door, then drove home at five miles an hour, sticking to back roads, with the horse trotting next to him the whole way. When he got home, his shocked parents asked what exactly his intentions were with… what’s-his-name?

“He doesn’t have a name yet,” Dad responded.

“Let’s keep it that way,” his mother said. “Because he isn’t staying.”

It never mattered how many times I’d already heard the stories. Dad kept me enthralled, and I would always drift off to sleep with images in my mind of my young father driving a car with a horse happily trotting next to him, a raccoon nestled in his shirt, or a wet boy and his dog admitting that he had disobeyed his parents.

When circumstances that shall be covered in a later entry led to my father exiting my life when I was nine, my world was spun into a sad oblivion. Somehow I knew that I wouldn’t see him again for a very long time, and the weight of that realization pressed heavy on my heart. It was then that I began to settle into a new normal of abandonment and daddy issues.

In spite of the chasm my father’s disappearance left in my life… or maybe because of it… I was very successful in business. It was made abundantly clear to me that neither my mother nor father would support me in failure. The year I left for college, my mom moved into a studio in a high-rise in downtown Cincinnati. At the same time, my father had remarried and had begun a new family. I didn’t have a landing pad. Failure was not an option.

And so, a professional success I was. Personally, I was a mess, suffering from years of rejection and self-esteem that scraped the pavement like a turtle’s belly.

Eventually I reunited with my father, but I was hard on him. I didn’t think that his disappearance in my life was my fault, but I definitely took his failure to return as a rejection. He didn’t work to find me; I had to find him. That fact simultaneously pissed me off and made me curious. I wanted answers. I needed to know how a father could leave his daughter at the most vulnerable time in her life. He knew that I had been molested, but rather than make the move to protect me, he found it easier to leave and not look back.

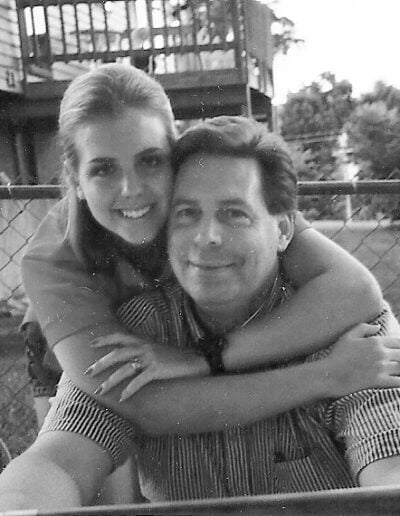

When I managed to find him, the first thing he said to me was, “What do you want? Money?” Foolishly thinking that he would be as excited to hear from me as I was to talk to him, I was taken aback by his question and innocently answered, “No… I just want my dad.” I conjured the memory of our precious bedtime routine and declared, “I won’t stop calling. I just want to see you.” I knew that we could save our relationship. I believed in the power of paws.

When we did finally reunite, I looked at my father in awe. Did he always have that gap in his front teeth? Was that always the build of his body? He had subtly aged. There were lines around his handsome face that weren’t there when he was telling me about Scamp. But one thing hadn’t changed: his sky-blue eyes were like looking into a mirror. We were cautious with one another… at first. But soon enough, curiosity got the best of me and I had to know why he never made an effort to find me.

My father was not a willing participant in my inquiries. He wanted to let the past… remain in the past. I consistently put my childhood in his face and demanded answers. But my father didn’t want to give answers. He simply didn’t want to talk about it. He wanted to act as though my childhood, and all the bullshit that ensued when he left, was a figment of my imagination. One time he tried to shut down my probing by saying, “There is a reason that the rearview mirror is so small compared to the windshield.” He had no interest in going into my childhood, even though ignoring the rearview mirror meant that I had been rear-ended numerous times.

I was hard on him for a long time, until neither one of us could take any more battery. I finally gave up on my interrogation. But after years of demanding answers, he was guarded around me, as I was with him.

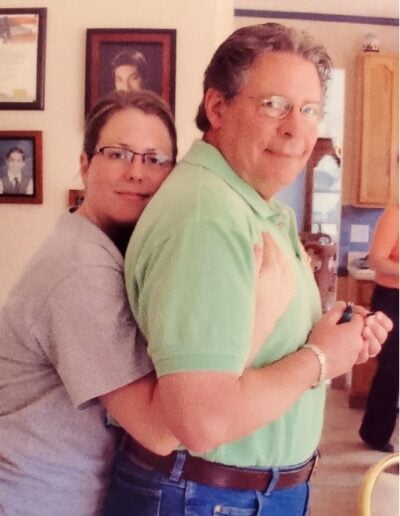

My father and I played golf together in the fall of 2018 and I could tell that he was… off. I had moved from being combative with him to being protective of him. I realized, too late, that my father hadn’t left me out of malice. He’d left because he was too tender to fight for me.

In the middle of our golf game, I told him to take some ibuprofen and play nine holes instead of eighteen. But because our foursome also included my brother and husband, he couldn’t resist the competition and ended up beating all of us… even while, unbeknownst to all of us, a disease was eating away at his bones.

Two weeks after our golfing weekend, he called me to tell me that he had cancer, and it’s one of those moments that is inked onto my brain like a regretful tattoo. I immediately tried to stabilize the situation. “It’s okay, Dad,” I said. “You’re okay. We’re going to get through this.” I had no idea how advanced his cancer was, nor did I care. I truly believed we were going to get through it together.

I dropped everything. I was a vice-president in the trust department with a prominent national bank. But I let everything slip: goals, meetings, clients. Subconsciously, I was determined to be everything that I had needed from him, but didn’t get when I was a kid. I would be there for him, come hell, high water, or stage 4 cancer.

I skipped out of meetings to take him to doctor appointments. I logged onto bank calls but put it on mute in the background while I made meals for him. When I was at home, I was there… but I wasn’t. My mind was with him. I would think, “How is he taking this? How is he processing this? How is he feeling? Is he scared?” I wanted to take him into my arms and tell him animal stories.

One day, after a CT scan revealed that his spine looked like it was “moth-eaten,” I put him in a wheelchair and told him to wait while I went to the pharmacy within the hospital to get his pain meds. I handed over the prescription, then searched the gift shop for something to distract him while we waited. I found a book full of animals in funny human positions. There was a little pink pig with a bow tie posing for his portrait, a baby chick dressed like a bunny for Easter, and a dog wearing cat ears. We went through the book together while we waited for his name to be called over the pharmacy’s intercom. He would laugh at an image of an animal, then wince in pain and try to shift the pain away with no success. In that moment, a winning lottery ticket for me would have been an end to his pain.

“Look, Dad,” I said, trying my best to distract his brain from the messages his body was sending. “Look at the raccoon. Does he look just like Rocky?” My dad turned to me with devastated sky-blue eyes and a sad smile.

“That little bandit face,” he said.

“I know,” I said, then pressed my forehead to his. It was in that moment we both knew that he was going to die.

Soon after that, it was determined that his cancer was too far advanced, and he was sent home with hospice care. We were told that, “You will find that this experience is a gift.” I remember thinking, “What the fuck is so wonderful about watching my father die a slow, horrible death?” But then the reward did in fact come…

During the first night we had him at home in the bed that hospice had provided, he was disoriented and pumped full of drugs. As a family, we tucked him in… much the way he had done for me forty-one years earlier. Then the rest of us convened in the kitchen, the room adjacent to his bed, thinking that he was fast asleep for the night. We ate, drank, and talked. In moments like that, no matter how heavy the circumstances, laughter finds its way into the situation, like rain clearing an old cobblestone sidewalk.

In the midst of our gathering, we heard him call, “Audrey?” Everyone froze and waited for further instruction. It came again. “Audrey?” My brothers and I sprinted to his bedside.

“Dad! Are you okay?” we asked in unison.

He pulled off his CPAP mask and asked, “What time is it?”

We answered, “It’s ten o’clock, Dad.”

Clearly bewildered, he said, “Oh. I thought it was morning. How long have I been asleep?”

“Only about an hour, Dad.”

He pondered that for a bit, then looked at me and said, “I woke up because I heard your laugh, and it was like music to my ears.”

I felt like someone had punched me so hard in the stomach I couldn’t catch my breath. I had to leave the room while my brothers saw to it that Dad got back to sleep. I went into the kitchen and collapsed. The grief was all-consuming and came in wave after wave.

Most of the pain came from watching my father waste away. But it also felt like a floodgate opened and suddenly I was arrested by anguish. I felt like I had played hide-and-seek with sadness all my life, and now it had suddenly found me. It reached down into my toes and found disappointment as a child, embarrassment in junior high, and heartache from ended relationships as an adult. It found my suicidal thoughts and my most tender insecurities. It found my fear and taunted my success. It even found every commercial I had watched showing abused and abandoned animals or a bald-headed kid suffering from cancer, their skeletal eyes lined in dark circles. The absolute worst vision, though, was that of my father walking out the door when I was a kid. He was leaving me again now, and just like before, there was absolutely nothing I could do about it.

What I could do was worry only about the outcomes I thought I could affect. I could try to see him as much as possible and worry about my career later. I could control my facial features when he told me that he thought he was improving. I could consistently work on my strength so that lifting him didn’t cause my back to seize up. I could make the meal he was craving, and I could tamp down my emotions when it was time to tuck him into bed. I could make sure that when he was gone, I could live with the mirror reflecting his sky-blue eyes.

He died on a Sunday morning. I wept over his body, finding it hard to believe that there wasn’t any breath left to take in his lungs. I caressed his face and moved a stray strand of hair off of his forehead. I whispered, “Go find Rocky and Scamp,” then backed away from his body.

I notified a family friend of his death, and she said, “Pardon my Native American shit. But make sure a door or window is open so that his soul can make its way out.” I slid the back door open, just in time to see a possum scurry into the woods behind the house.

I dream about my father all the time. I dream that he beat his cancer diagnosis, and that science marvels at his recovery. I dream that he walks around a corner and sees me anew, the way I saw him when we were reunited. And in my favorite dream, we simply sit by a fire pit and talk about raccoon markings. I see him almost every time I look in the mirror. I’m noticing that as I age, I look more and more like him, and that is just fine by me because my soul forgave him when he said, “I heard your laugh, and it was like music to my ears.”